Amongst the general population there is a near insurmountable divide in cultural mores and social values. I have many very friendly relationships with Korean people, and encounter very little hostility, but there is a persistent sense I am being confined to the periphery, a token acquaintance, an outsider. As a calloused and experienced outcast, this has little effect upon my spirit, but can well imagine it being difficult for the young and unjaded among us.

South Korea at this time has about a 3% immigrant population, and of that 3%, most are East Asians, (Chinese or Japanese), making them indistinguishable in physical appearance. The visibly apparent foreign population here is far less than 1%, There are so few of us I can go days, even weeks, without seeing another undeniably non-Korean.

These encounters have been among the highlights of my existence here, as isolation is the great equalizer in all things pretentious and social. I have had my most extensive interactions with other teachers from England, Canada and New Zealand, and of course Americans, but I’ve also had the chance to socialize with Cambodian construction workers, Russian factory laborers, an Indian engineer, a few Iranian programmers, Vietnamese furniture makers, and one particularly raucous evening with the Turkish consular staff, all serendipitous happenings as a result of the granfalloon of our anomalous appearance.

This conspicuousness from the general population gave me significant trepidation about raising my daughter here, because aside from sexual or physical abuse, there is no greater unkindness than the outcasting of a child during his or her critical developmental phases. I was especially mindful of this since my early school years were spent mostly rejected, antagonized, and bullied, events that are largely responsible for some of the more persistent and dementing monsters that haunt my weaker moments. If I should have a legacy it is to have reared a positive, confident, and radiant human being, untroubled by the self-loathing and detachment that is familiar to me.

There is a steady stream of young visitors in our home, pajama parties, and a constant exchange of electronic messages. I am pleasantly surprised, even thrilled that she has found a place among the tribe.

There have been of course outlier experiences, people pointing out her differences, for example. (There is a Korean word, “Honyol”, which literally means “half-blood”, which Koreans insist is not offensive, but I am skeptical, and resent the semantic implication nonetheless.) Her reaction to honyol seems indifferent, but again I wonder. She is well aware that holding an American passport carries with it a level of social prestige (not to mention a “get out of jail free” evacuation should Kim Jong Un have a particularly foul-tempered day—one of the finer perks of American citizenship here).

She is getting an outstanding education (South Korea is ranked toward the top of OECD for quality of education), and her teacher has reported she is not only well-liked and popular among her classmates, but a top performer academically as well.

There is a high certainty that her social adjustment and acceptance is exceptional, as she has inherited mostly Korean features: dark, straight hair, dark eyes, and the epicanthic fold. (I believe epicanthic fold is known in most academic circles as “slant eyes”.) She is fully bilingual, even favoring Korean over English, and is in short, passably Korean in an undeniably tribal society.

I have read of many less favorable experiences on expat forums and other sources. Hines Ward, the Pittsburgh Steelers legend, was the offspring of an American GI and a Korean mother, and suffered isolation for his appearance, eventually settling in the US because of it. Iis a sad irony when an “African-American” man needs to escape to America for greater racial equality.

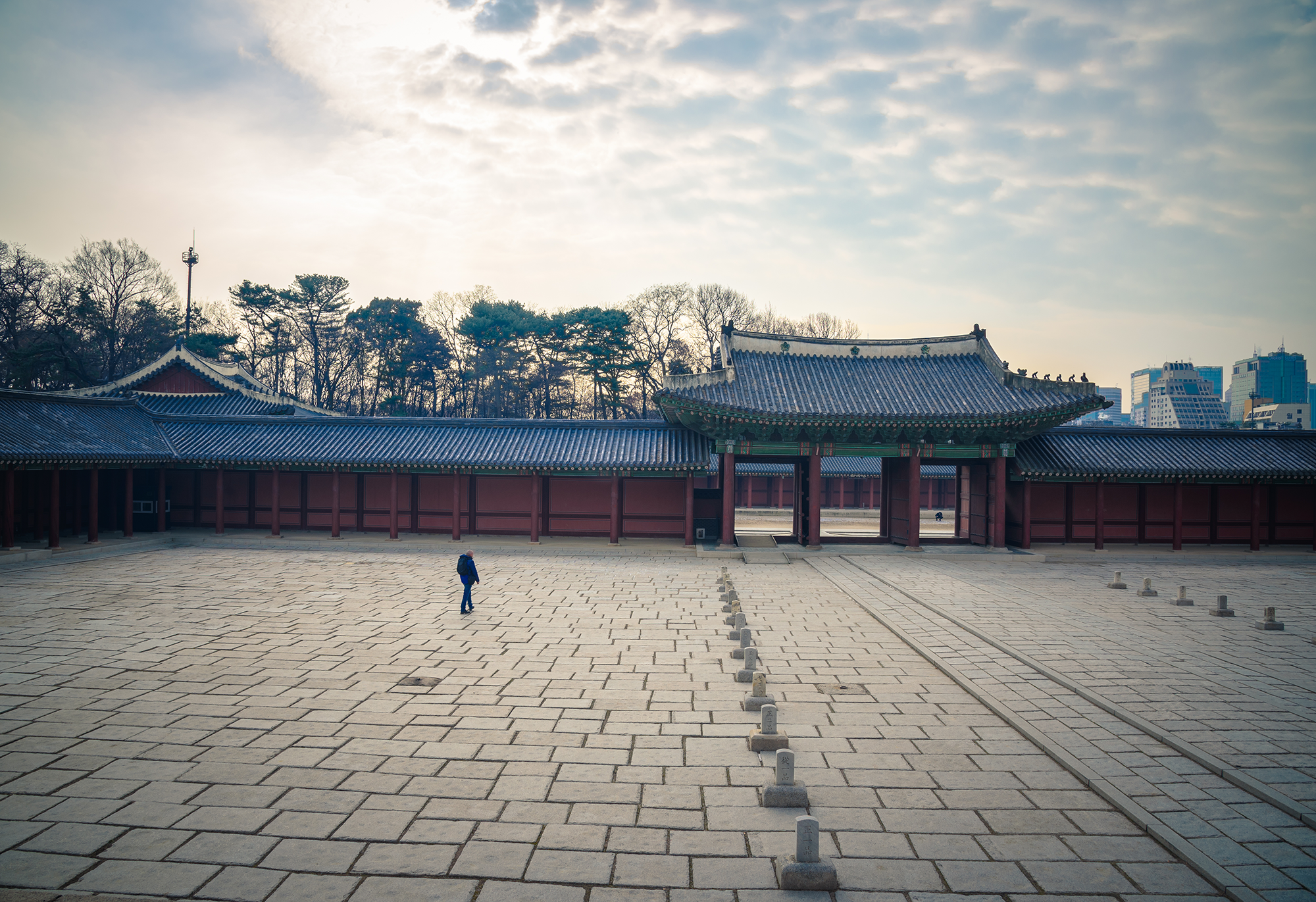

Although there has been significant social progress in my time here, the situation is far from ideal. I harbor a hopefully-not-too-naïve optimism it will improve, and foreigners will be accepted as members of Korean society in the approximate future. Although South Korea unquestionably adheres to a vigorous sense of nationalism and a steadfast desire to preserve traditional values, there has been a gradual and begrudging acceptance of the concept of globalization and its consequences. Fraternization and genetic dilution are the necessary consequences of a seat at the table of great economic powers.

While many Koreans relish in the prospect of partaking in the American Dream, where there is a perceivably higher ceiling, immigration carries a risk of failure and uncertainty. Korea, on the other hand, offers the familiarity and comforts of home, but also a sense of existential tediousness. The choice will be hers to make in seven years, and I am pleased that she feels Korean enough to make that choice difficult. It would seem for the time being, my legacy remains intact.

0 Comments