0085 | August 19, 2019

Climate Change: Who Will Suffer and Who Will Profit

The effects of climate change will not be evenly distributed. Some landscapes, cultures, and peoples will suffer more than others. And some people will profit from that suffering. Who has a responsibility to deal with that suffering?

| C.T. WEBB: 00:19 | [music] Good afternoon, good morning, or good evening and welcome to The American Age podcast. This is C. Travis Webb, editor of The American Age, and I am speaking to you from sunny and a bit hot southern California. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 00:31 | Hello. This is Steven G. Fullwood. I am the co-founder of the Nomadic Archivists Project and I am coming to you from Harlem and it is hot here. I think it’s in the low 80s. |

| S. RODNEY: 00:41 | Hi. I’m Seph Rodney. I am an editor at the Hyperallergic art blog and recent author of The Personalization of the Museum Visit which was published by Routledge in May of this year. And I am in the south Bronx not too far from Steven so it is just as hella hot here as it is there. |

| C.T. WEBB: 01:00 | This is to remind our listeners that we practice a form of what we’d like to call intellectual intimacy, which is giving each other the space and time to figure out things out loud and together. We are back to our discussion– our long-form discussion on climate change. We had a brief detour last week and spoke about Toni Morrison recently passed. So the topic I believe this week are— we had talked about the areas hardest hit by climate change. So in the scientifically grounded speculations about where climate change is going to go, what it’s going to do to communities. Certain communities are certainly going to be more dramatically impacted than others so it’s a big planet at least from the human point of view. So Seph, Steven, we all agreed to kind of do some reading and find out since we’re not climate scientists, but we are concerned citizens. And as our former President said, “Citizen is one of the most important positions in a society.” I tend to agree with that in a democracy. So we have a responsibility to be informed citizens. So informed citizens, countrymen, what have you found? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:18 | I wouldn’t call myself so informed. I was reading some articles online and did some crunching, but Seph, do you want to–? |

| S. RODNEY: 02:26 | Yeah. I think I can start just by– I mean one of the things that occurred to me in looking at this was that it’s very plausible to talk about climate change in terms of things that are happening out there. A report released by the Global Climate Risk Index, released in 2015, subtitled, Who Suffers Most From Extreme Weather Events, talks about basically more than half a million people have died as a direct result of approximately 15,000 extreme weather events between 1994 and 2013. Okay. In 2013, the Philippines, Cambodia, and India led the list of the most affected countries. Part of my concern reeling off statistics like this is that I realize that particularly for a US audience, and most of our audience is going to be based in the US, that doesn’t necessarily cut a lot of mustard or have a lot of traction. |

| S. RODNEY: 03:35 | I think when you say things like the Florida Keys are very much in threat of disappearing, or half of– or maybe not half, but a significant portion of New Orleans has already been lost. And it’s very likely that we could lose the majority of it in the next 20, 30 years. I think that that has more purchase with people. So there’s part of me that wants to talk about the worst affected places. But I’m also cognizant of the fact that if I say the Maldives, if I say the Great Barrier Reef is dying off, that that won’t move the needle of public perception or the way your hearts respond. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 04:26 | This is powerful. Keep talking. Keep talking about this because I have something to say about this. |

| S. RODNEY: 04:31 | Well, I think if anything else, I have to say it’s that part of the issue– I mean we often come back to a kind of critique about culture, right? I suppose that’s inevitable. Part of the problem I have with the ways that we understand very complex issues like climate change is that we don’t as a culture generally understand them until they’re made personal. So Rob Portman, right? Republican senator, I believe somewhere in the Midwest. Very vocal about anti-LGBTQ policies and legislation until his son came out as gay. Then when his son came out as gay, he was like, oh well, I love my son. He’s a human being clearly. We need to rethink what we’ve been saying about LGBTQ people– |

| C.T. WEBB: 05:27 | This is the Cheneys too, right? I mean so Cheney is– Dick Cheney sort of straight-up the middle, as conservative as– as conservatives as conservative can be, but his daughter is gay. But they’re fine with the gay thing, right? So everything else, they have– |

| S. RODNEY: 05:42 | No, no. Right. We can bomb the shit out of people of color that we will never meet because American might equals right, but yeah, let’s go easy on the gay people for now, right? |

| C.T. WEBB: 05:53 | Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 05:53 | For now, because we’re actually just talking about my family. |

| S. RODNEY: 05:57 | Right. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 05:57 | We’re not really talking about policy. And maybe we’re just lip service in some ways because we have to see the policies sort of overturn. This idea of just– I don’t know if it really falls into the idea of American exceptionalism, but what we are really experiencing is my Marianne Williamson moment where we’re just not connected. And as a result of that fracturedness, and a result of being able to only see what is almost directly in front of you kind of nonsense, has really impacted our vision to see and to feel and to be empathetic. When I was a kid, I remember those Care commercials. As a kid, they’re in Africa and they’re showing kids in substandard, you know? There was no way to translate it for a child. We just knew that Africa was not a place to go. |

| S. RODNEY: 06:45 | Right. Right. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 06:46 | That’s all we got. So the teachers and our parents and other people, “Well, you better eat because there is some kid starving in Africa.” Really? There are children starving in the US. Do you know? So I don’t want to get too far off of my point, but this idea that really stops us from understanding I think the changes in the global climate really are just so indicative of so many other things that we failed at or that we have no capacity to build– I mean that we have the capacity to build, but don’t have the capacity right now. So starting off globally, it doesn’t do it. I mean I agree with you. |

| C.T. WEBB: 07:20 | Yeah. I think you’re right to point out the limitation of that story for most humans. I mean I think I feel too– I think I have too emotional responses to the standard oppositional responses to climate change and a responsibility to address it. So I don’t have a great deal of antipathy towards less sort of working-class Americans or working-class people in any country or culture that are not overly concerned with climate change because we just haven’t really– that’s not what our species does, right? |

| C.T. WEBB: 08:06 | We are good at assessing what’s in front of us, directly in front. Immediately planning for the future. How do we kill that lion that’s on the edge of the Savannah or whatever? And most of a working-class family’s life is circumscribed by what is immediately in front of them. How do I get to the next paycheck? How do I get to work? How do I stop my kid from being bullied, or how do I stop my kid from bullying? Whatever. And of course, you can mix in entertainments and shallow distractions and all that kind of stuff, and of course, that’s all true. So it doesn’t produce a great deal of animosity for me and I don’t expect people to care for things that are essentially invisible. It’s very difficult to care for things that are invisible. I have a– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 08:56 | Theoretical? Invisible, theoretical? |

| C.T. WEBB: 08:59 | Yes. Yeah. Yeah. That’s what I mean. I mean things that are– it’s not right in front of their face. I have a great deal of antipathy towards vested power interests that are preoccupied with short-term economic gains and preoccupations with commerce that understand the consequences and the effects of climate change. And not only refuse to do anything about it, maybe you can rationalize that because they’re responsible for jobs or whatever. But are also obfuscationists and do things to actively obstruct and prevent a more progressive, ambitious agenda, right? |

| C.T. WEBB: 09:48 | So for me, my animosity is targeted at those people. And for those people, I do think it’s reasonable to hold them to a standard of where are these going to be– where are these going to impact cities around the globe? They can think about commerce transnationally to import and export their products, right? They can do currency– they can factor the prices of their oil and natural gas on currency exchange markets to trade with Vietnam or Cambodia. But you’re saying that they can’t imagine what climate change is going to do to coastal cities? No way. No way. I don’t think those people get to be let off the hook. And I– oh, I’m sorry. Go ahead, Seph. You were about to say. |

| S. RODNEY: 10:34 | Well, no. What I want to say is that I’m mindful that we’re going a bit off-topic in that we’re critiquing what essentially are our attitudes and our outlooks. But we really want, I think, this episode to talk a bit more about what is actually happening in those places in the world that are feeling the very pointy end of the spear right now in terms of climate change. |

| C.T. WEBB: 10:58 | I was trying to boomerang– I was actually trying to boomerang back to that. |

| S. RODNEY: 11:01 | Okay. Sorry. |

| C.T. WEBB: 11:01 | Because you had said that it wasn’t– you had said that it was not very effective to talk about how things are going to be affected outside the United States. I’m saying we can talk about all of that because I think that the people that are responsible for these policies can– they do have the capacity to talk about what’s going to happen to Myanmar. What’s going to happen to Cambodia. What’s going to happen to low-lying coastal cities. To be very grounded in specific, Jordan, for example. One of the most water-stressed countries in the world is– already has extreme water shortages that are only going to get worse. And so anyway, I’m sorry. But yeah. I appreciate the reminder. I’m with you though. What are some other concrete examples of places that are going to be devastated by rising global temperatures? |

| S. RODNEY: 11:53 | So the Marshall Island– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 11:54 | The south. |

| S. RODNEY: 11:54 | Go ahead, Steven. I’m sorry. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 11:56 | I’m sorry. I apologize. I was– you go ahead. I’m going to– I’ll wait. |

| S. RODNEY: 12:00 | I was just going to talk about the Marshall Islands. The Marshall Islands they say that by mid-century thousands of them could become uninhabitable because the sea levels could rise by 16 inches. That’s a foot and four inches. That’s significant. So I mean what we’re talking about is places like them. Just I mean and the Maldives and the Marshall Islands I think are looking at a similar scenario. But they will literally be lost. They will be part of the sea. |

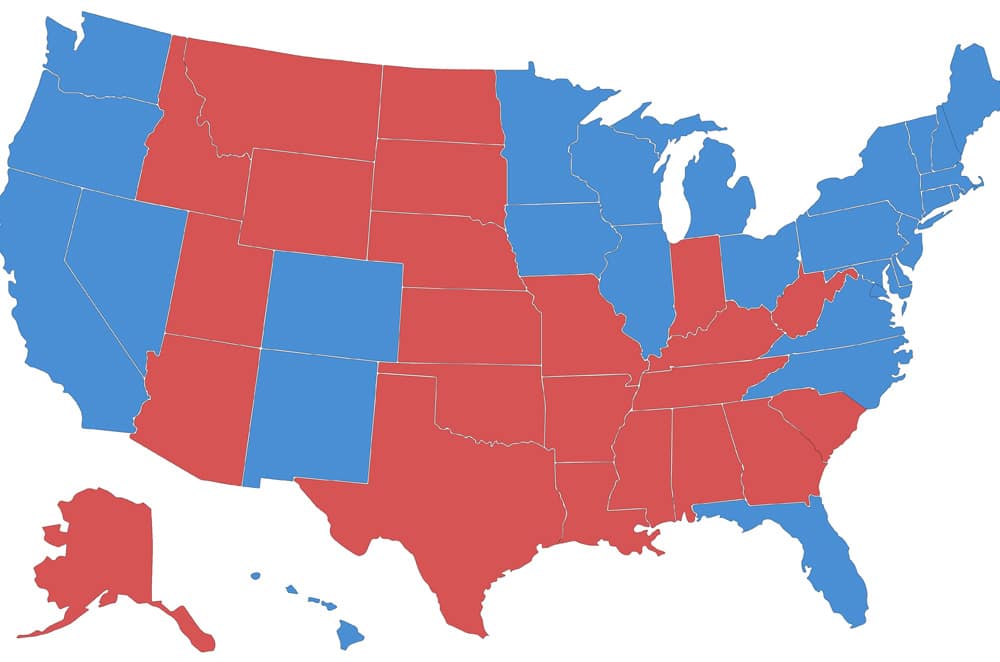

| S. FULLWOOD: 12:34 | Oh, I was just thinking about the South. The different parts of the South. Texas, Louisiana. I mean there are places where they are already experiencing this. I mean you mentioned earlier about Louisiana, or at least the lower parts of Louisiana, the New Orleans and whatnot. But there are places that are feeling the economic stress. They are feeling the effects of global climate change in real-time like all of us but in different ways, in a more stressed area. We’re talking about agriculture, mortality, the lack of energy, low-risk labor, high-risk labor, coastal damages, property crime, violent crime. These things have all been impacted to and linked to climate change. And that these red states, these red states specifically, these are the Republicans who do not believe or are not moving the needle on making their state’s more compliant or– not compliant, but just aware of their deniers, their climate change deniers. So you’ve got the policies that are really fucking these people’s lives up more. |

| C.T. WEBB: 13:41 | And the people with vested interests in those areas, right? I mean I– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 13:44 | [crosstalk]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 13:45 | Yeah. I remember the story made the rounds around the 2016 election, or I guess maybe just after Trump got elected. And his climate change policies, they were obvious, but sort of the consequences of that kind of denialism. And across the board, it’s red states in the United States that are going to be the most impacted by climate change. The ones that are the least prepared and the least willing to do anything about the change that’s coming for coastal communities, for water supplies, for food supplies, and all the other things that you listed. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 14:26 | And we’re seeing it in real-time where these places are being destroyed by a rise in tornadoes or a rise in hurricanes. And the response is so slow, like snail slow. We need to do this. There’s all arguing about who needs what relief. Puerto Rico still fucked up. Puerto Rico is still fucked up. Because it hasn’t made the news cycle recently except for throwing out the governor? Yeah. I think the governor. Throwing him out [crosstalk]– |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:54 | That’s right. Three times I think. They’re on their third governor now or something like that I think. |

| S. RODNEY: 14:58 | But you know– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 14:59 | I don’t [inaudible]– yeah. It was an odd moment. Yeah. Still, but go ahead. |

| S. RODNEY: 15:02 | But you know what’s weird is that I’m looking over the statistics, I’m struck by the fact that you have two sort of extreme weather conditions, or I should say– well, yeah. They are kind of weather conditions happening at the same time, or one is a weather condition and another is just sort of effect, is you have in Madison, Wisconsin– you have extreme drought happening in certain parts of the year, right? But in places like Louisville, Kentucky, you’re getting extreme precipitation so that you get flooding. So I guess it’s kind of hard for people to wrap their heads around the fact that in one part of the country you could have climate change actually be registering as a lack of water, right? And anecdotally, I’ve read about this too and in certain parts of– farm parts of the country. But in other parts of the country, they are literally getting flooded out. |

| C.T. WEBB: 16:05 | Yeah. It’s the extremes that are the problem, right? So I mean there is nothing– it’s not like there is an infinite reservoir with which to capture torrential rain. At a certain point, the rain itself– the precipitation becomes the enemy and as a site of destruction as much as if not more so than extreme drought. And then the effects are erosion. So if all the topsoil is eroding, if the mechanisms for that climate for capturing rain are being eroded in torrential rain, when the drought comes there is even less nutrition in the soil for it to recover. And it’s this sort of cascading effect. Again, to stay with Seph’s reminder to be specific, I was remembering just Steven your comment about the South– does North Carolina, is that officially– that’s north or south? Does North Carolina [inaudible]–? |

| S. RODNEY: 17:03 | That’s south. Oh, that’s south. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 17:04 | South. [crosstalk] south. |

| S. RODNEY: 17:05 | [crosstalk]. Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:06 | So the North Carolina state legislature– whatever it was six years ago, seven years ago, or whatever, literally passed a law that you could only use historical shoreline records. You could not use projected shoreline records for legislation around real estate and real estate pricing and stuff like– so it literally, it was a willful, intentional effort to protect and prop up real estate prices for what? 10 years, 5 years, 12 years? Whatever– |

| S. RODNEY: 17:41 | And then the bottom falls out. |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:43 | Yeah. And you better believe that the people that are doing that are selling their real estate when they need to sell their real estate. Before any of that stuff bottoms out. There are predatory creatures at the top of our economic food chain that are making a lot of money off of what we would call red state– I mean– we would– red states are red states. But kind of what I would call ignorance. Not that the people are ignorant, but– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:19 | No, I know what you mean. |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:19 | –ignorant in the way that all humans can be ignorant, right? I mean we all have our blind spots. And there are people that are making tremendous loads of money off of this. Yeah. Anyway, so. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:29 | Okay. I just want to add to that very briefly and then can get more specific per Seph’s request. And that is are we living in– and I mentioned this before in a past podcast about this apocalyptic nature of living. Going to die anyway. We might as well make as much money as we possibly can. I was on the train yesterday talking to a friend and there was someone who comes on the train in New York City and they try to sell things and say this is for the homeless. If there is anyone who’s hungry I have food here, dot, dot, dot. But if you’d like to make a donation today. They were recently found out as frauds. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:02 | Really? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:02 | And I just go– I mean the grift game in the world is amazing. There is shit that I have not even heard from people who would make money for a small amount of time. And I don’t like saying we’re doomed. But I just feel like there is something to not feeling like there is a future to preserve. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:24 | I think you’re right. I absolutely think that that sort of nihilism is at the heart of a lot of that. And it’s at the heart of our– by his own admission, our current president. He talked about that– some helicopter crash killed some top-level executives in the 80s or 90s and Trump executives. And he did an interview not long after that where he was like, “This is just what life is. It could be taken away at any moment. None of it means anything.” That kind of nihilism is absolutely at the heart of that apocalypticism, fatalism, whatever you want to call it. Yeah. I think that’s absolutely on the right track. [inaudible]. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:07 | And per that specific information regarding climate change and how it’s affecting us, apparently June was the hottest month on record ever. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:24 | July. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:25 | Oh, July was. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:25 | They think– Well, I think June– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:26 | It was July. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:27 | Yeah. July. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:27 | Oh, that makes sense. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:28 | Just the one that just passed. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:29 | Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:29 | Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:29 | Yeah. That must [crosstalk]– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:29 | It was July. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:30 | Ever. Ever. That we’ve ever recorded. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:33 | Yeah. That’s just ridiculous. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:35 | Provided that we have only certain amount of information that we can use to measure whether or not it was the hottest on record to signify what you just said about the real estate records. It’s just like really? It’s the suppression of information. It’s astonishingly– it’s mind-boggling what people will do to live in a certain way. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:53 | To live in their own ideology. Yeah. Absolutely. To– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:56 | Oh, definitely. |

| S. RODNEY: 20:57 | Yeah. Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:57 | Yeah. It’s a little wonky, but there is– it’s a very rich and fruitful area of human– or of social science and humanistic scholarship right now which is that– and they would have pushed back on my term– on my characterizing it as ignorance. There are actually forms of knowledge that are counter epistemological. So you actually– that it’s not as if it’s just ignorance of climate change, but that literally, there are counter knowledge networks that work against dominant knowledge networks, or specialized knowledge networks, or whatever you want to call it. And that there are actually– their internal logics and there are internal facts to these counter epistemological networks. And they’re very resistant to change, right? It’s not as if sunlight as knowledge disinfects them, right? They actively are resisting that kind of information. And I think it’s a good reminder– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:08 | We’re about to get a lot of– yeah. I think it’s a good reminder. I apologize. I was just thinking about the disinfecting part. We’re about to get a lot of the goddamn sunshine. I see how we’re about to get a lot of fucking sunshine. |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:20 | That’s right. Yeah. It’s– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:21 | Goodness gracious. |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:23 | So other areas of– I know that Europe, for example, has been– there’s been a recalcitrant heatwave that sort of set in this summer. It’s not that they don’t have hot days, but that it’s persistent and it’s long. And they don’t have air conditioning the way that most of the United States does. And so extreme weather leads to more deaths that you had brought up at the beginning, right? That actually– the elderly are more vulnerable. We had talked about on previous podcasts the elderly, the poor are more vulnerable to these kind of changes. High rises in New York are probably going to be fine. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 23:12 | Hey. I mean but then there is also the spread of disease, the decreased water, wildfires are going to continue to rage. And then it’s the ecosystem that’s really breaking up because of– we’re talking about– if I think Lake Erie in 2007 didn’t freeze for the first time, and so that affected fish populations, it affected migration patterns [crosstalk] birds. |

| C.T. WEBB: 23:35 | This is 2000–? 2007? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 23:37 | Seven. 2007. |

| C.T. WEBB: 23:37 | Seven. Okay. All right. Okay. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 23:38 | According to this article I read. Yeah. So it’s just affecting the different ways– I mean it’s really affecting our thinking and not in the best ways. The better ways is we need to do something about this, or let’s recycle. Carbon emissions, let’s bring them down. Let’s do renewable sources of energy. And then there is, “Ah.” There is that. |

| C.T. WEBB: 23:59 | Right. Right. Right. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 24:00 | So yeah. And try not to be in the, “Ah,” so much because it will cloud your thinking and it won’t allow you to think of things. But I mean we could be hit by a solar flare at any time. Thank you, Jupiter, for these kinds of things and the magnetic poles or whatnot that hopefully won’t shift anytime in our lifetime. But there are– yeah. There is a lot to consider, and that was a big mishmash there so I apologize for that. |

| C.T. WEBB: 24:26 | No, no. It’s okay. It helped me actually think of a response to my own sometimes saying when approached like, “Well, New York high-rises are going to be fine, etc.” Yeah. I mean historically, that– I mean we know that– I mean dramatic climate change shifts have happened historically, and there there is active research around the effects of that. And one of the areas in which they think climate change had a dramatic impact on the established elite society was in ancient Egypt. So the Hyksos in the 17th century it’s argued may have been driven across the Aegean into Egypt, which led to the fall of that civilization because of dramatic weather changes. And so people as we know, if you watch Fox News, people don’t just sit around and watch the world end. They move. They get up. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 25:26 | No. Right. |

| S. RODNEY: 25:27 | Right. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 25:27 | Right. |

| C.T. WEBB: 25:27 | And they used to jump in ships or they walked. And now, they get in boats and vans and they go places where they think it’s going to be better. And I don’t say that to defend the rhetoric around invasion or any of that kind of stuff. I don’t believe that, but they do. Steve Bannon and that lot of people actually do read the things that I am talking about and they do believe that those areas where climate change is going to be hit the hardest, they do believe that that will drive volatility and potentially invasions. That’s the worldview that they are operating inside of. Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 26:18 | Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 26:19 | Yes. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 26:20 | I mean– yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 26:21 | That’s sobering and dangerous at the same time. I want to kind of begin to round out the conversation today by saying or by asking what we want to talk about next. And I think we have a sense now of the places in the world, how they’re vulnerable, in what ways they’re vulnerable, what places in the world are most vulnerable. Should we talk about what we can do practically? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 26:54 | I like that. |

| C.T. WEBB: 26:56 | So there are two things I’d like to– one is practically, and I would just add into exploitation, right? I mean these places are vulnerable to exploitation and that’s kind of what we’ve gotten at. I mean if it’s sort of rounding out the conversation. That is what we’ve gotten at, right? I mean that these places are vulnerable to be exploited by people that are in power and do understand. What we can do, I definitely want to talk about that. I’d also like to talk about lowering the temperature on the rhetoric around climate change because there is very good– the Berkeley climate change project, which is data-driven and very well-respected, and their research has begun to be incorporated in larger projects, it’s more concerned about certain things that are not often talked about, and less concerned about things that are often talked about. |

| C.T. WEBB: 27:55 | So there is a way to complicate the picture that I think makes room for what we can do. It makes room for not hope in a flat naive way, but hope in that like, no we can get our– we can put our shoulder to the wheel and we can do some things to mitigate what’s coming. So I’d like to talk about both of those things. And then a third one is I’d really like Seph to talk about how climate change and its preoccupation has shaped themes in the art world, in contemporary art, and how you’re beginning to see the representations of that in artwork and preoccupations with artists, so. |

| S. RODNEY: 28:45 | Yeah. Okay. All right. Yeah. Let’s do that. Maybe next week we can talk about the Berkeley report and see where that takes us. |

| C.T. WEBB: 28:56 | Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I would like that. |

| S. RODNEY: 28:58 | Good. |

| C.T. WEBB: 28:58 | Steven, do you have anything? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 29:00 | Oh, no. Actually, I’m just writing down climate change and archives. I’m like, “Let me think about that.” |

| C.T. WEBB: 29:05 | Oh, yeah. Absolutely. Yeah. Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 29:07 | So it’s like, “Oh, okay. That’s something I think I know, or know a little bit about but definitely need to learn about.” So yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 29:12 | Yeah. Thanks very much for the conversation |

| S. RODNEY: 29:15 | Indeed. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 29:16 | Cool. |

| S. RODNEY: 29:16 | Thank you. |

References

**No references for Podcast 0085*