Fathers, Part II: How Do We Create Possibility from Pain?

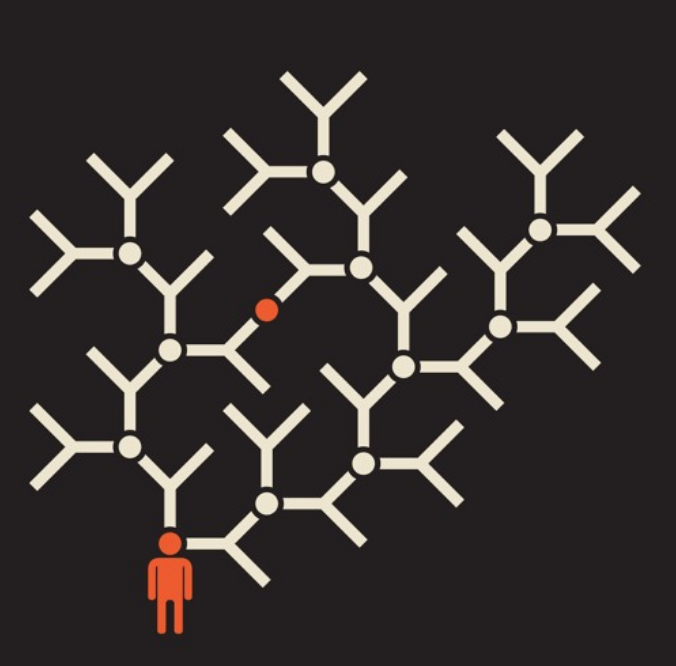

TAA 0037 – C. Travis Webb, Seph Rodney, and Steven Fullwood continue their discussion about fathers. Picking up from last time, they consider what is and isn’t possible in our intimate relationships. From fathers to history, we are born into dynamic contexts that both injure and inspire us. What tools do we have to manage these overwhelming forces?

| C.T. WEBB 00:19 | [music] Good afternoon, good morning, or good evening and welcome to the American Age podcast. Today, it’s a full house again. Seph Rodney, Steven Fullwood, how are you, gentlemen? |

| S. FULLWOOD 00:27 | Howdy like. Howdy like. |

| S. RODNEY 00:28 | Hey. What’s going on? Happy to be here. |

| C.T. WEBB 00:31 | So thankfully, this week we’re talking to people again [laughter]. And two weeks ago, we had our first discussion on fathers, and Seph suggested towards the end that we pick it back up for a part two because we were getting to some meaty stuff and I think we all were pretty enthusiastic about that. And Steven, you closed the podcast by saying that you had a great response to Seph’s question. So I’m going to invite Seph to reframe what he asked, and then Steven if you want to just take us in and give us the great answer. |

| S. RODNEY 01:02 | So the question I had posed at towards the end of the last podcast on fathers which was the week before last, was we had gotten to this point where we recognized that our fathers in various ways– Travis’s so less than perhaps Steven’s father or my father. Didn’t really have a grasp– a complete grasp of the fact that they didn’t have certain tools for child rearing and didn’t know that those tools existed, and therefore didn’t know how to get them. So my question was if you’re in a position where you don’t even realize that there are such things as tools in your tool belt for rearing a child, how do you go about turning that corner? How do you go about realizing that need, and then going out and finding those tools? |

| S. FULLWOOD 01:53 | Well, the answer I had two weeks ago, I’ve been able to sort of augment it since then. But the first thing that came to my mind when you suggested that Seph or asked that question, was for fathers to ask themselves– and it’s based on a presumption. Why does it hurt? Why does it hurt? Why does it feel awkward? Look at your relationship to your own father, if your father was in the picture. Look at your relationship to other men. Direct contact with other men in terms of who you work with, who are your friends. Really start to look at the ways in which you understand being a man because I think that goes to the core of it. |

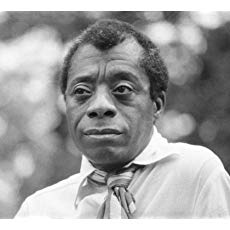

| S. FULLWOOD 02:44 | What I was able to do because I– so I was a part of a panel discussion this past Tuesday at NYU. It’s the republication of James Baldwin’s first and only children’s book, Little Man, Little Man. And it was published in 1971, so it’s 47 years now. And the book is about his nephew, TJ, who happened to be there who lives in France, but also came with his family. Gave a really wonderful kind of personal take on, “Wow. I asked my Uncle Jimmy to write a book about me and he did.” And so one of the things that we talked about in the conversation was this idea of innocence, which made me think of an essay by James Baldwin called The Preservation of Innocence. And in this essay, he frames what it means to be an American ideal in terms of masculinity and femininity. And how these roles have effectively locked us out of who we really are, right? |

| S. FULLWOOD 03:45 | And so I posted something on Facebook just a moment ago and referring to the previous conversation about fatherhood. And so there’s a line from the essay that really caught me which is, what are we to say who have been already betrayed when this boy, this girl discovers that the knife which preserves them for each other has unfitted them for experience? And I think the core of it– Baldwin explores this idea of masculinity and manhood through his fiction and non-fiction over the years, and I think it’s someone’s dissertation project, I really do. There’s another essay called Here Be Dragons which is more suited for our point today and it’s this idea that masculinity it’s an ideal that you can’t grow in it. You can’t develop, and you can’t move. And so when I was thinking when people think about how to be a better father, then maybe what they should look at is why it hurts. And so I’m just going to read something very briefly from Here Be Dragons by James Baldwin, which is collected and is non-fiction as well as in other editions. The idea– |

| S. RODNEY 04:59 | And I just– sorry. I just want to interrupt really quickly just to make sure I nail this down for myself and for listeners. When you say Here Be Dragons, you mean dragons as in the mythical fire-breathing creature, right? |

| S. FULLWOOD 05:09 | Absolutely. |

| S. RODNEY 05:11 | Okay. Cool. All right. |

| S. FULLWOOD 05:13 | The American idea of sexuality appears to be rooted in the American idea of masculinity. The idea may not be the precise word for the idea of one’s sexuality can only with great violence be divorced or distanced from the idea of the self. Yet something resembling this rupture has certainly occurred and is occurring in American life. And violence has been the American daily bread since we have heard of America. Let’s get down to a last part of it which– or another part of it which is the American ideal than of sexuality seems to be rooted in the American ideal of masculinity. This idea has created cowboys and Indians, good guys and bad guys, punks and studs, tough guys and softies, butch and faggot, black and white. It is an idea so paralytically infantile that it is virtually forbidden as an unpatriotic act that the American boy evolve into the complexity of manhood. So taking Baldwin’s take on it and my own thoughts about this whole innocence project, is that it doesn’t– how do you build fathers out of this mass of neurosis? How do you do that? And I think it goes to pain. Why does it hurt? And so something I’m floating right now and just thinking about, but I’d be interested in seeing what you guys have to say about it. |

| C.T. WEBB 06:34 | So I don’t know that I can tease out the various thoughts I had in response to that. One practically speaking, I think that when habits of mind become so entrenched it’s difficult to tease out their root. And so I don’t know that men that injure their sons and intimates would even identify themselves as being in pain. And I think the pain gets covered over at such a young age, and there is such a deep habit of using that strategy whether it become anger or outrage or whatever it may be that that moment that reflects of pain isn’t even sensed by the person. And I thought a lot about what Seph– Seph pushing back last week– or a couple weeks ago on that he did the mixing and the baking and that– of course, the expansion of our sympathies is an unqualified good, but there are limits and there are acts, there are choices, there are people that we can’t reach with our sympathies to influence their actions. |

| C.T. WEBB 08:00 | And I basically think I agree with that. Even though I am kind of perpetually hopeful in the possibility of that expansion because you can never know what reality someone might wake up to. I was speaking of terrible fathers. Apparently, Steve Jobs was just an absolute piece of shit apparently. The autobiography– or the biography. I’m sorry. Lisa Jobs, right? His daughter came out. And some of the stuff that he did to her just, oh, my God. Awful. I mean there’s really no reason to recount it here, but the reason I bring it up is because at the end of his life apparently, she said he kind of broke down in tears and said you didn’t deserve anything that happened to you. And her stepmom said I don’t believe in deathbed conversions. Well, the thing is I do believe in deathbed conversions. I do believe that the sheer– I think that we as– and then I’ll kick it back because I’m not going to be able to segue to some of the other thoughts I had on what you said, Steven. But– |

| S. FULLWOOD 09:13 | Okay. |

| C.T. WEBB 09:13 | –I’ll just finish up this thought. I think that as human beings, men and women, we have evolved and are calibrated to be somewhat accurate instruments of the world that surrounds us. The social world and the environment that surrounds us. And that there is a collective injury that happens when you have denied that reality over such a long period of time that the imminence of death can bring us to some kind of realization of the pain that we have caused other people. And the wrong that we have waged against others. So anyway, I’ll kick it back to you guys, but. |

| S. RODNEY 09:53 | So I want to say a couple of things. And I want to give a real-world example from my own life. So just to kind of round things out. One of the things that Steven has suggested in a very considered response to both Baldwin and that question of what to do if you don’t have the tools, is he suggested a kind of– the way I read it is a therapeutic response. So when the thing happens with the father, someone somewhere in his life says to him, “Where’s the pain? Where does it hurt? Why does it hurt?” Right? And you’re saying Travis, well that therapeutic response may not be enough because the person, the father may not even have access to himself enough, so he’s not self-aware enough. He’s so embedded into masculinity so deeply the masculinity that Baldwin, I think accurately describes as kind of– well, toxic, right? And the kind of place from which we understand and sort of put ourselves on the continuum of sexuality. |

| S. RODNEY 11:02 | That person isn’t able to do that work even if they’re given the opportunity to a sort of therapeutic situation which could be just a cup of coffee with an aunt, right? She sits him down, she says, “Where does it hurt?” And he can’t come up with an answer. So my question is– and I’m asking the same question essentially, but in a different way using my own experience with my father. Was I remember – and I told you this story already Travis – that sometime when I was six or seven– I wasn’t any older than eight I think. And I was in New York, and my parents had immigrated to New York City in North Bronx from Jamaica. And it was some day, I think I was sitting either on my father’s lap or very close to him. And my father has very heavy brows. My face is somewhat different. He has very heavy, prominent forehead. |

| S. RODNEY 12:04 | And I was reaching up to just touch it, to just kind of trace the ridges on his face just because I think as a child I was just curious. I wanted to know my father in that way. And it’s a very sort of intimate gesture reaching to touch another man’s face, and he slapped my hand away and he hit me in the head with his knuckles and I started to cry. And my mother turned to him and said, “Why would you hit the child like that?” And I don’t remember what my father said, but he made a gesture, he made a sound, he conveyed that it was uncomfortable for him to have me touch him like that. And my question is if someone had come to him in that moment and said, “Mr. Rodney, where’s the pain? What would cause you to do that?” Would he be able to say an answer? And my guess, my educated guess knowing my father is that he wouldn’t be able to. I mean maybe given enough time, maybe enough in being asked that question enough times, maybe. But I mean– I want to say this too. |

| S. RODNEY 13:24 | In the podcast, in the first iteration of this I had started off by describing my father as a narcissistic asshole. And I wanted to be clear with people why I said that. And part of the reason why I said that is precisely these kinds of things that happened to me when I was a child. That he was physically abusive with me, he was angry most of the time, and he took out that anger a lot on me. And then the world really did revolve around him. So I don’t know. When I asked the question I think– or rather I don’t know what would’ve sort of interrupted that circuit. I don’t know what could have intervened to get him to look at himself and see that he was actually in pain. And clearly, he was. I mean that’s the story I told the last time. Indicated his own relationship with his own father was awful. He was deeply wounded by that. And to round this off, there may be deathbed confessions that are really redemptive in some way, which is what I think you were saying, Travis, but you can follow-up on that. Maybe not redemptive, but they– |

| C.T. WEBB 14:38 | No, thank you. I don’t necessarily think redeemable, no, or redemptive, no. But– |

| S. RODNEY 14:41 | Right. Right. No, but they’re at least– |

| C.T. WEBB 14:44 | Authentic. |

| S. RODNEY 14:45 | Yes. |

| C.T. WEBB 14:45 | They’re authentic. Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY 14:45 | They’re at least a moment where that person comes to understand his own– he becomes accountable to himself for what he’s done. My question then is, but so what? Because the child is still injured, right? The child still has to put him or herself together because the deathbed confession is worthwhile to the person who is dying, but is it worthwhile to us? |

| S. FULLWOOD 15:12 | I think so. I definitely think so. I also feel like I want to challenge this idea of a deathbed confession or conversion worth an acknowledgment or a breath or some kind of fuller thing because I’m sure Steve Jobs in our example carried this with him. I’m sure he did. I’m sure there was some recognition of it in his own mind. But at the same time, with this whole idea of a conversion, no. I just feel like he reckoning with his own mortality finally let this thing go. He breathed. He ahhh. Almost like a weight. I’m imagining all this, but I do think the work is critical. And I want to quote something that you said, Travis, about this idea that you’re perpetually hopeful for that experience, right? Which I think is one of the reasons why I write and think for my own benefit, but also for thinking about putting it out there, putting out on different platforms that it’s not only possible to change– I mean this is life or death really for a lot of people. It’s as simple as that. So I mean it’s really important that we think more about the possibility as opposed to the probability of someone not changing. |

| C.T. WEBB 16:36 | Yeah. So I mean the distinction that you draw between possibility and probability I think is a good one. It’s probably a space I live in most of the time. I think that’s how I try to move through the world in dealing with people that are difficult to deal with is possibility as opposed to probability. That being said, I don’t necessarily know that that’s where wisdom rests because if you move through the world always thinking of the possibility I mean that essentially makes you naïve. |

| S. FULLWOOD 17:18 | Oh, I disagree with that. |

| C.T. WEBB 17:19 | And– What was that? Were you going to say something? |

| S. FULLWOOD 17:22 | I completely disagree with that [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB 17:24 | Oh, okay. No, please. Okay. So if you always move in a space of what might happen whether good or bad, it seems to me that you run the risk of not being sufficiently grounded in reality. So to give a very dark example, Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated. He was shot dead, right? I mean just, bam. Gone. The Civil War was fought, and then Reconstruction rolled it all back, and in some cases made it worse. I think that I don’t want to live without possibility. But to not live in the reality of what I would call– and you might push back on that. What I would call the reality of probability is just a problem. I won’t say more than that. I think it’s a problem. |

| S. FULLWOOD 18:36 | I as being relentlessly and just by default I’m optimistic and live in the possible, I think I speak for myself that I think I’m still very intellectually curious and interested and respect science and respect probability and all those things. And I think those things are a jumping off point for things that can happen. That the statistics say– It makes me think of how excited people are about the blue wave right now. Oh, the blue wave, the blue wave. And I go, 2016 everyone? Do you remember this? So I’m like okay. There is some evidence there that we might be. But I see– |

| S. RODNEY 19:24 | Yeah. Don’t get it twisted [laughter]. |

| S. FULLWOOD 19:26 | Don’t get it twisted [laughter]. But I like holding all the possibilities without being constrained to one or the other. Do you know? Because I think I would be immobile as a person or as a thinker if I didn’t think that there was something beyond the thing that we call reality or something that we call, this is just how it is. This is just how it is. And that’s just an impulse. That’s just ever since I was a kid, it was just an impulse. So I respect all kinds of ways of thinking about it. But I don’t think it makes you naïve. I think for me, it excites me, and it makes me more intellectually curious. Yeah. And loving. |

| S. RODNEY 20:04 | I just– |

| S. FULLWOOD 20:05 | [crosstalk] and loving. |

| C.T. WEBB 20:06 | No, no, no. No, I agree with that actually. But this allows me to weave in an anecdote that I had that occurred to me two days ago that I wanted to be able to share if it worked itself into the conversation. I wasn’t sure if it would. But to illustrate the enormous weight of what I will just kind of e.g. as probability, i.e. history, i.e. culture, i.e. sort of the collective circumstances we are born into, right? That’s what I’m calling probability. And possibility meaning the kind of space that we create here on the podcast to try and actually come into some sort of intimacy with one another’s thoughts and share that with people. I was driving near my house and I passed a junk van, like get rid of your junk. There was an advertisement on the side of it. And it was College Boys Junk Removal, it was the name of it. |

| C.T. WEBB 21:09 | And the immediate thought in that nanosecond before my critical reflective consciousness came back. In that nanosecond, when I saw College Men Junk Removal, I thought of a white male. In that nanosecond before all of the years of reflection and reading and conversation and training could come into it. Now, and I have those tools, right? I can come back and go like, “Whoa. That was kind of a really stupid racist thought that just flitted through my head,” right? But there it is, right? I mean and that is to me, that is the weight of probability and the enormous amount of effort it takes to overcome that with imagination and possibility shouldn’t be underestimated. |

| S. FULLWOOD 22:15 | Oh no, not at all. |

| S. RODNEY 22:15 | Okay. Okay. But fair enough. But I want to stay on this track we started out on and try to pin down some answers to that initial question. So so far what we’re saying is that, okay. We all have the tools to think in this space of possibility, clearly because we’re doing the podcast, right? And that’s as Travis pointed out, this is precisely where this thing exists. Great. And we now have a sense of how we got here. The kind of energy and– well, actually, to be clearer, the kind of curiosity, the kind of self-awareness, the kind of sense that we’re all unfinished projects and we want to keep working on them throughout the rest of our lives. We all know that these are the tools that to a great extent got us to where we are today, right? |

| S. FULLWOOD 23:20 | Absolutely. |

| S. RODNEY 23:21 | Travis, Steven, me. This is what we did. This is who we are. These are the tools that we have at our disposal and a few other things, family infrastructure and good friendships, la, la, la. |

| S. FULLWOOD 23:34 | Right. |

| S. RODNEY 23:35 | But okay, so let’s assume that our fathers, for the most part, did not have access to those things, right? No, clearly, I know given what both of you have said to me. Both your fathers did not come from circumstances where they had I would guess only one or two of those things I just mentioned, right? They may have had an innate curiosity or a drive to be better in the world, but they didn’t have a lot of family infrastructure, non-great friendships, la, la, la. And my question again is, okay, so you lack all those things, right? How do you get to the point, right? And when do you get to the point? I mean is it when your son is just born? Is it when he’s 10? Is it when he’s 20 and you deal with him as you would another adult that you begin to see, oh, oh. I see how you formed, and I can see my influence on that thing that you’ve become. Oh, that’s who I am as a father. |

| C.T. WEBB 24:47 | Yeah. Damn. |

| S. RODNEY 24:47 | Does it happen then? |

| C.T. WEBB 24:49 | Right. |

| S. FULLWOOD 24:49 | It could. It certainly could. And so the very brief example I’ll give is that– and this is all what I’m imagining. So Timothy DuWhite, who recently put on a one-man show at the Dixon Place, and his one-man show was called Neptune. And it’s based on the idea that people who are hard to love, the HTLs, need to go find a place called Neptune to be loved, right? And in the play, in the one-man show, his family plays characters. They are not exact lines to the characters, but one he’s talking to his father. His father says, “I blamed myself when you became HIV positive.” It was an interesting sort of rich characterization. He’s playing all these different parts. The first night he gave the show, his father came to the show. And he didn’t know if he had come on time, and so when he’s thanking everybody at the end of his show he goes, “I also want to thank my father. Is he in the audience?” And his father goes, “I’m here son. I’m here.” I’m here. And in the post board conversation that Timothy and I had about it. The place gets quiet. And I love to imagine the very thing that we’re talking about, the sight of possibility. Of somebody seeing their son who I imagine is radically different. These are two different people. Could see some of the things that his son is going through and maybe change happens there. Do you know? |

| C.T. WEBB 26:17 | So I got to say, that’s a world full of one-man shows because there is a lot of work that has to be done. So I mean I– |

| S. FULLWOOD 26:27 | But that’s just one side. |

| C.T. WEBB 26:29 | Honestly, I basically feel like we’re kind of the same page with this stuff. I mean may those shows increase. May that work continue. I want to be engaged in that work. Seph and I in an early podcast kind of talked about that in relation to some of the work of Ta-Nehisi Coates and critical of that. I was critical of that, but I don’t want to rest on cynicism. I think it’s a kind of weakness, at least in myself I see it as a kind of weakness. I don’t want to live in that space. I don’t want to teach my sons to live in that space. I want to make them feel like they have a responsibility to go out and be better human beings for themselves and the people around them. And oh, my God is the world difficult and hard to bear. And I just– |

| S. FULLWOOD 27:25 | Well, when you go wide like that, yeah. But you go local, and then you see what you can do locally [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB 27:31 | Right. Right. Right. Yeah. You live in New York. That’s easy for you to say. |

| S. RODNEY 27:35 | Well, to that point, I mean so we don’t end on a– well, I don’t particularly want to end on a cynical note either. And I’m not sure I’m fully convinced it can end on a positive one. I mean I want to kind of end with a question which is I had– so intermittently throughout the years, my father and I have fallen out of touch. Not fallen. That’s wishy-washy. I have refused to deal with him. I have not made any contact with him for several years at a time because he has treated me the way he has. And recently, I think it was two weeks ago? Maybe a week and a half ago he reached out to me again after several years. I came back from London in 2011, and at the time my mother would often visit the house I grew up in. She lives in Jamaica, but she would often come back and visit to get various things and spend a little bit of time in New York. She no longer does that. |

| S. RODNEY 28:35 | Anyway, I would see her at that house. And I ran into my father once, and he asked me what I was doing, la, la, la. And I really just didn’t want to talk to him. I didn’t want to deal with him at all. And I said, “Look. If you want to get in touch with me, if you want to actually pick back up where we left off, my suggestion is you find a therapist. You arrange a time for us to sit down with that therapist together and we can do that.” And he, of course, did nothing about that for six years. Nothing. I had to call him once to see about making repairs on my mother’s house in Jamaica. I think he may have tried to call– actually, he may have called me once during that six years and I hung up on him. And then he called me again two weeks ago and he said, “Well, I want to reach out.” And I said, “Why?” And he said, “Well, I want to give this father-son thing a try.” Something like that. Like I want to be father and son. Mind you, one of the last conversations I had had before I left for London was essentially him thinking that I was gay because I have gay friends, Lawrence and Mingus, and [crosstalk]. |

| S. FULLWOOD 29:41 | Well, yeah. Obviously, therefore. I mean– |

| S. RODNEY 29:43 | Right. Right. It must be, right? He had said to me that if I ever find out that you’re gay, then you don’t have a father and I don’t have a son. And I was like, okay. That’s my– |

| S. FULLWOOD 29:51 | Really? |

| C.T. WEBB 29:52 | Bye. |

| S. FULLWOOD 29:53 | Aw. |

| S. RODNEY 29:54 | Yeah, yeah, yeah. He’s that kind of person. I mean that’s like I said, narcissistic asshole. |

| C.T. WEBB 29:58 | Good luck to you, sir. Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY 30:00 | But right. But he [inaudible]– |

| S. FULLWOOD 30:01 | And good day to you, sir. |

| S. RODNEY 30:03 | What? |

| S. FULLWOOD 30:03 | And good day to you, sir. |

| C.T. WEBB 30:05 | Yeah. That’s right. Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY 30:07 | So he reaches out, he says, “Father, [inaudible] father and son.” And I said, “Well, why now?” And I said, “I need to know. I don’t understand this. Why now?” He’s like, “Well, why now? Why are you asking that?” Because I don’t understand this. You had years. You had years to reach out to me. Why now? That’s a reasonable question to ask. I just don’t understand it. And then started to go off and I hung up on him again. I realized that one of the things that I’m really unwilling to do at this point in my life, as much as I understand that forgiveness is really crucial to being able to move past this relationship which is ultimately never going to give me the things I wanted from my father. |

| S. RODNEY 31:00 | What I want to hear from him is some sort of acknowledgment– or rather what I realize is that for me to move forward with any sort of real conversation with this person, I need to have baseline. I need to have an acknowledgment of there being something fucked up. You were a shitty father. I need that acknowledgment, or at least some sense of here is an opportunity to work on something and I’m actually going to– I don’t even understand where you’re coming from necessarily. But I’m going to do the work to meet you on the ground that you’ve laid out as being the place where we need to meet. So we need to meet in a therapist’s office. Okay. I’m willing to do that. Even if you weren’t able to say to me, “I realize I made some mistakes.” Whatever. But at least say, “I can meet you here.” |

| C.T. WEBB 31:53 | So Seph, can I respond to that with a possible as opposed to the probable? |

| S. RODNEY 31:58 | Please do. |

| C.T. WEBB 31:59 | What about just asking him for that? And saying if you want to have a conversation like this, I need you to acknowledge how difficult it was to grow up with you, and I need to have that conversation in front of a professional. And see what he comes back with. |

| S. RODNEY 32:15 | Okay. I can do that. I can do that. I can try. I can text him then. |

| C.T. WEBB 32:19 | Probably he’ll come back with some shit, but you never know. But you never know. |

| S. RODNEY 32:27 | And to be completely fair and honest with myself, I don’t even know if at this point in my life I need that relationship. To be transactional and a kind of mercenary emotional capitalist about it, what the fuck do I get out of this? What is the point of this now? |

| S. FULLWOOD 32:47 | But you’re never just one thing, Seph. You’re several different boys. You’re several different men. And maybe somewhere inside of you, that’s not coming to your consciousness at the moment that would really like to have that relationship maybe. Maybe. |

| C.T. WEBB 33:00 | Yeah. And– |

| S. RODNEY 33:01 | Maybe. |

| C.T. WEBB 33:02 | –you got that phone call the week before you proposed the podcast on fathers. |

| S. RODNEY 33:08 | Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD 33:08 | Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 33:09 | So clearly, there is some emotional potency there still. |

| S. RODNEY 33:16 | Yeah. No, of course, I mean my relationship with my father is one of those. So we began the conversation couple weeks ago talking about how fathers are often wounded. They’re often as Steven kind of alluded to at the top of this session, where’s the pain? There’s pain in me around my father clearly. It’s hard. I mean it’s part of who I am was forged in those formative years dealing with a father who was constantly angry. And it took me probably close to 40 years to figure out that I was super angry all the time. And it’s only been in the last few years with therapy and the help of good friends and good girlfriends actually, that I’ve been able to get a hold of that. So yeah. I’ll take your advice. I’ll try it. I’ll reach out. I’ll see what happens. |

| C.T. WEBB 34:26 | All right. Well, maybe we’ll have to have that Fathers, part three is that goes off, so. |

| S. RODNEY 34:29 | Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD 34:29 | Oh, yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 34:30 | Steven, do you want to close us out? |

| S. FULLWOOD 34:33 | No, I think what Seph said is the closer. It really is. |

| C.T. WEBB 34:37 | All right. |

| S. FULLWOOD 34:38 | Thank you for that, Seph. That was really– |

| S. RODNEY 34:40 | Yeah. Thank you, guys. |

| S. FULLWOOD 34:41 | Thoughtful. |

| C.T. WEBB 34:42 | Yeah. I appreciate the conversation. Thank you for listening. And Steven, thank you. I noticed you advertised the podcast on your Facebook feed which I appreciate. Thank you very much. |

| S. FULLWOOD 34:51 | Yes. |

| C.T. WEBB 34:52 | So thank you everyone for listening. |

| S. RODNEY 34:53 | Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 34:55 | The podcast will be posted on Monday at 10 AM and will be posted on Monday at 10 AM going forward. So you can pick it up on SoundCloud, and we’ll be posting it on iTunes towards the end of the month. You can also find it on theamericanage.org. Thanks, Seph and Steven, and I’ll talk to you guys next week. |

| S. FULLWOOD 35:11 | Thank you. Great talk. |

| S. RODNEY 35:13 | Okay. Take care. |

| C.T. WEBB 35:14 | Bye-bye. |

| S. RODNEY 35:16 | Bye. |

References

First referenced at 02:44

James Baldwin

James Baldwin (1924-1987) was a novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic, and one of America’s foremost writers. His essays, such as “Notes of a Native Son” (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-twentieth-century America.

First referenced at 08:00

Lisa Brennan-Jobs

0 Comments