0062 | March 10, 2019

White Supremacy:

Who is responsible for educating “whites”

What does it mean to say, as Malcolm X famously did, that it’s the responsibility of whites to educate themselves? If each group is responsible to educate only those who are already a member of that respective group, how can we forge a coherent national identity?

| [music] | |

| C.T. WEBB: 00:19 | Good afternoon, good morning, or good evening, and welcome to The American Age podcast. My name is C. Travis Webb, editor of The American Age, and I’m speaking to you from Southern California, which is not sunny today, but is still Southern California [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 00:33 | Which is better than how I’m doing here in the South Bronx. I’m Seph Rodney. I’m an editor at Hyperallergic, the visual arts blog. And I’m on the part-time faculty at Parsons. Yeah. It’s cold. It’s like 25 degrees here, which don’t make no sense. I mean, I know it’s winter, but still. I’m from [laughter] Jamaica. It don’t make no sense. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 00:58 | I was going to say, he’s from Jamaica, so he’s mad [laughter]. He’s mad a lot in winter. Yeah. I’m Steven G. Fullwood, and I’m one of the co-founders of the Nomadic Archivists Project, a consultancy company that helps people of African descent help organize their individual and organizational archives. And I’m coming to you from Harlem. And I believe in humanity. I can’t wait to get to our conversation today. |

| S. RODNEY: 01:23 | Amen. Amen. Bring it. |

| C.T. WEBB: 01:23 | All right. Okay. So this is a reminder, listeners, that we practice a form of what we like to call intellectual intimacy, which is giving each other the space and time to think together out loud and hopefully get somewhere new. We’re continuing our conversation on what we titled white supremacy, although early on, we had a slight correction that all three of us, I think, kind of agreed with and took up, which was white misanthropy. And so we’re continuing that conversation. Today we’re going to let Steven take the lead. I think he has a number of things for us to kind of puzzle through. And at the end of the program, white misanthropy will be gone. It will eventually disappear and be solved, so [laughter]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:07 | I couldn’t wait to get in on that. I was so happy that you said that. That’s like, “Yeah. It’ll be gone?” So I am going to open this conversation up today by saying thank you, Seph and Travis, for engaging me. So the idea for this particular perspective, I’m considering what white misanthropy does to white people, as opposed to racism. What kinds of sort of mental, emotional, spiritual sort of impact does it have on someone who calls themselves white? So I sent Travis and Seph a bunch of resources to look at. And one of them, the woman who put it in my head, was Toni Morrison. It was the 1993 interview with her about her book Jazz, and she was on Charlie Rose, and although the interview’s much longer than the excerpt I initially sent them, what she’s doing is– Charlie is asking her about– so she’s considering the idea of the Clarence Thomas nomination at that point. And Clarence Thomas, African-American male, conservative who was elected to the highest court in the land, the Supreme Court, she had noted early in the interview that no one had really thought about him as a brilliant person. They just kept on emphasizing black. And what he did was sort of use, rather than– in his own words – and actually, I’m going to mess them up. So sorry. They’re not verbatim – that one black person has to follow the trajectory of their lives, and either they choose violence, or they choose profit. And he basically chose profit, essentially. He became a conservative and so forth. |

| C.T. WEBB: 03:48 | There are two options if you are black, just so you know [laughter]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 03:51 | Just so you know. You can become a Supreme Court Justice one day. And so what she said was– and he was asking her about her perspective on that, and she says, “Well, essentially, it’s not how does she feel about ascension or upper mobility, but how does he feel about it? How do white people feel?” And she was like thinking, “No, not you yourself, Charlie, but how does a white person feel about racism?” Because it feels crazy. It’s not logical. And she goes, “If you have to– if you need to have your foot on someone else or someone else on their knees, what does that mean to you? What does that mean?” |

| C.T. WEBB: 04:31 | On their knees [inaudible]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 04:34 | And so without race, without that thing, what are you? Are you any good? And at the end of her sort of moment, she goes, “That’s a very serious problem.” And to her, white people have a serious problem, and they need to figure out what they’re going to do about it and to leave her out of it. And that’s sort of the jumping off point for this particular conversation. Because I was curious. I was like, “We’re always thinking about race and white supremacy, white misanthropy as impacting other people. But what does it do to the body of a person who is also raced, was also there?” So I wanted to start there by asking a couple of questions of both Seph and Travis. |

| And one is, when you heard her say that or when you were engaged in the other readings, what were some of your thoughts about this idea? What does it do to someone who’s white, white supremacy, white misanthropy? | |

| S. RODNEY: 05:32 | One of the things that first came to mind– I hope you don’t mind me jumping in, Travis. |

| C.T. WEBB: 05:37 | No, please do. Please do. |

| S. RODNEY: 05:38 | One of the first things that came to mind just now was actually the film Monster’s Ball, which stars Billy Bob Thornton, I think, and, I mean, Halle Berry, right? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 05:52 | Yes. Yeah. Billy Bob Thornton. |

| S. RODNEY: 05:56 | And I saw this film a long time ago, but I remember one of the issues with the character played by Thornton is that every morning when he wakes up, he throws up. Every morning he wakes up. Before he goes out into the world to do whatever he needs to do, he vomits. And I think that, in an obvious way, was a reference to how sick he was. But I think as a metaphor, as analogy, perhaps, it works, in that every day, his life– the life that yawns before him in the morning, right, that he prepares himself to go and manipulate, go and work through, is so daunting to him, is so awful to him that he nervously throws up whatever was in his stomach when he contemplates that day. |

| S. RODNEY: 06:59 | And I do think of that in relation to the Toni Morrison interview with Charlie Rose in that I think when she asked the question, “What are you without racism?” I have to think that there are people like Thornton’s character or people like The Proud Boys who tomorrow, if they didn’t have a black or Latino or Chicano or, I don’t know, Laotian other by which to compare themselves– or to which to compare themselves, and always come out taller, right, always come out better, always come out stronger, then I wonder if that the day that would yawn before them on that morning, right, when we were somehow all gone or somehow just diffused into, let’s say, a sort of generalized soup of humanity– I wonder if the day would yawn before them with all that terror and all that sense of, “I’m not sure who I am to be today.” I wonder if that’s part of what– I’m wondering if that’s what would confront them. That’s what comes to my mind. But again– not again, but I realize as I say this that this is really just a drawn-out psychological speculation, because I don’t know anyone like that. |

| C.T. WEBB: 08:39 | Well, we do. I mean, so certainly, it’s a speculation. But we do– I mean, Seph, and I mean, you read voraciously. And I know it made the rounds maybe a decade ago, maybe a decade plus, the rates of mental illness that increased dramatically in the former Soviet Union and after the dissolution of the Soviet Republic and suicide rate spikes and all the rest of that. And we have the opioid crisis in the United States. It seems pretty clear to me that we know what happens– I don’t want to say most, but we know what happens to a lot of people when they lose their grand narrative. Particularly men, but certainly, women are susceptible to it as well. But more particularly men, I think. When they lose their grand narrative, the world becomes disorienting, and life and its ever-present ability to bore you [laughter] becomes overwhelming, and depression sinks in, and violence follows, particularly with certain personality types. So I don’t think your speculation is– I don’t think you’re just spitballing. I think there’s a real reason to think about it. |

| C.T. WEBB: 10:03 | Two things occurred to me. One I will bookmark, but I can’t not bookmark it, which is just because that’s me. I don’t think that there’s anything particular about a white supremacist narrative that is disorienting to its disillusioned than would be disorienting to any other grand narrative that disorients people. I think that there are a large– there is a large segment of the population that is currently invested in a kind of racial-political narrative, even if it’s on the side of politics that we might agree with, that would absolutely fall apart if it was shown to them that race didn’t play a significant factor in filling the blank in their misfortune or whatever it might be. There’s just no way they could hear it if that were the case. I’m not saying it is. But I’m saying there’s no way they could hear that and still maintain their perch in the world. But I don’t want to– we can talk about that if you want, Steven. The thing that I– my personal reaction to the Morrison thing, up until the brilliant comment I’m there with her 100% on, I get a little irritated when I hear people say, “It’s not my problem to help white people.” |

| S. FULLWOOD: 11:36 | Oh, okay. |

| C.T. WEBB: 11:37 | “White people need to do it themselves.” Because the underpinning of that idea is an atomized notion of the self, which is the very metaphysics which they would reject. No one is in the world alone. No one. There are no white people over there that need to go do their thing and figure their shit out. You can tell, I’m actually getting irritated. That’s a bullshit construct. That is a construct that I would attack intellectually and emotionally. I completely reject it. And when a person of color or a person who identifies with an ideology that advocates for the rights and enfranchisement of colored people, when they say, “White people, go figure your shit out,” they are pushing a “white, Western, limited, atomized narrative.” And so– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 12:35 | I would completely disagree with you. |

| C.T. WEBB: 12:38 | Okay. Please do. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 12:39 | I’m really dead on with your– because you have dismissed a lot of things [inaudible] whole cloth. And things that I do appreciate about– because I think at the bottom of what you’re saying is humanity, a collective humanity. What I think about– I think that there are layers to it. I think the first layer is people have been so invested in a particular kind of whiteness for a while that where– black folks have tried to be human and continue to be human. There are whites who try to be human, who are human, who work with that idea. But I know that one of the issues that I think someone who’s invested in whiteness, however it manifests– and the artificial construct, yes– that they need to pull that apart for themselves. Your job isn’t to save someone else. Your job is self-preservation first. |

| C.T. WEBB: 13:39 | So why are– hold on. Okay. Okay. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 13:39 | And [inaudible], because I’m thinking about the community. Because what you’re suggesting– I mean, your irritation with it, I would be more irritated if I saw more movement. I would be more irritated if at the bottom of– at the end of the day, survival wasn’t my first priority. I would be– |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:01 | It’s not your first. Steven, survival’s not your first priority. Come on. Come on. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 14:03 | No. My survival in a white supremacist, white-misanthropic society is self-preservation. |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:12 | But you do not move through your day in a survival mode. Come on. Come on. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 14:17 | But what you’re doing is you’re qualifying the idea of what survival is. Now tell me what you think it is. Tell me. |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:24 | Sure. Survival meaning that your very existence hinges on the decisions that you make on a day-to-day basis. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 14:37 | So if a cop decides to take me out for walking across the street or me pulling my phone out of my wallet– I mean my pocket and thinks that it’s a firearm? |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:48 | If a cop decides to take anyone out. I don’t understand, but. I don’t understand– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 14:52 | But you understand that black life– |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:53 | No, no. No, no. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 14:55 | You understand that black life is a lot more tenuous in the US and continues to be than your regular white person. Right? |

| C.T. WEBB: 15:02 | Okay. So now let’s pause on that. No, because neither you nor I know that because the research is not clear on that at this point. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 15:09 | The bodies stack up. |

| C.T. WEBB: 15:09 | At the likelihood of a black male being on the receiving end of a murder by a police officer via firearm, the jury is out. Where it has been studied, it seems that white men are more likely to be shot. Now, do I –? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 15:28 | That’s because of the population– |

| C.T. WEBB: 15:29 | Wait, wait. Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 15:31 | That’s because of population, dude. Don’t talk disproportion. |

| C.T. WEBB: 15:32 | No, no. Steven. Steven. Okay. I will very happily send you the research for– I mean, that’s just not accurate. What is accurate is the likelihood that you are harassed, that you are on the receiving end of police harassment or detainment or the rest of that. That absolutely is true as a black male, and probably a black female too. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 15:57 | So when we talk about survival– when we talk about survival, we’re also talking about mentally. We’re not just talking about me being killed or physical harm. We’re talking about mental. We’re talking about mental deaths. We’re talking about that kind of harm. Do you understand what I mean? |

| C.T. WEBB: 16:10 | Okay. I do. I don’t think they’re the same. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 16:15 | That’s fine. That’s fine. |

| C.T. WEBB: 16:16 | I don’t think they’re the same. I think that people that grow up in an environment in which their lives are actually at risk in a substantial way on a daily basis are working under greater psychological stress and threat than someone whose life is not at wager every day. I’m with you if you want to talk about sort of abstractions and all of our lives are precarious. And of course, I believe that. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 16:51 | I don’t think they’re the same set of data, and I don’t think it’s the same thing. I agree with you about someone who is in a concentration camp or someone who is in war. Those are different stats. But we’re talking about the mental thing that continues to build and develop and really kind of sharpen and think– I don’t think that it is my responsibility to help white people get over white misanthropy. I think my job is to be a human. I think it’s their job to look at themselves. |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:22 | Okay. So let me– |

| S. RODNEY: 17:24 | Can I jump in? Can I jump in real quickly? |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:26 | Can I ask one question, and then I’ll let you? Okay. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 17:26 | Sure. |

| S. RODNEY: 17:27 | Sure. Go ahead [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:28 | Okay. So would you– let me just ask it a different way, because I don’t want to hide what I’m actually saying. Why are you okay with pushing a self-reliant narrative for white people but not okay with pushing a self-reliant narrative for people of color? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 17:48 | Well, I think I push– self-reliant, what do you mean? |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:48 | You are saying whites must rely on themselves in order to deal with– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 17:54 | I’m saying whites need to get over their mental issues around racism. That’s what I’m saying. |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:58 | Okay. Who are these white people? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:02 | The people who identify as white. What are you saying? |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:04 | But I’m saying who are they? Who are the white people? Now, if you want to talk about the poor boys, you want to talk about the– okay. Yes. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:11 | I’m talking about your regular, run-of-the-mill person who might consider themselves European, American, and any ethnicity, who considers themselves white. |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:18 | How many people have you encountered in your life – and then I’m sorry because Seph wanted to jump in – run around thinking about themselves as white in the way that you are describing? How often does that –? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:33 | You mean whites who would identify –? |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:35 | How often does that –? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:36 | Whites who would identify as being white? |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:39 | Yeah. How often is that– in your interpersonal experience– I don’t mean what’s happened to you like what you may read that way in a particular passing social encounter, because your view of the world is going to be colored by your ideology. I mean on an interpersonal, intimate level, how have you been affected by a “white person” that represents a “white ideology” that impinges on you as a person of color? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:09 | When I worked at the New York Public Library, sir. That’s just one example. I’ll go into it, but I won’t go into it that deeply because I don’t want to bring up names. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:17 | Okay. Fair enough. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:18 | But I’ll say that the ways in which– where I worked, the ways in which people who considered themselves white were questioning whether or not there were certain kinds of black people, what kinds of folks or what kinds of history we should collect, because they didn’t understand it. And that is a white privilege thing, where they can’t think past their own ideas or think past that this particular kind of culture’s worthy of being collected. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:44 | Where the people of color in unanimous agreement with –? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:48 | Black people. Let’s just go to black people. Let’s not go to people of color. Let’s go black. This was a black institution where I worked at. And I worked within– |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:54 | Okay. I’ve no problem with saying black. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:56 | Right. Within a larger white institution. This is the New York Public Library. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:58 | Okay. So were all the other black people at the institution in agreement with your position that these white folks were incapable of seeing the value of what was being collected? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:10 | Not everybody, because everybody thinks differently. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:13 | Okay. So there were diversity of opinions. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:13 | No, no, no, no. There may have been dissent. Of course there will be, but. I get where you’re going with this, I think. But what I’m saying is– you asked me a question about how I was impacted by someone who thought– didn’t really think of themselves as white, but when it came to collecting and preserving black culture, they had– “Well, I’m not sure if this person is,” and so forth. I have the experience. I know this to be a fact that this material was worthy of collecting. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:41 | Okay. So I get that. And I’m not even– So I’m not weighing in at all on the value of the collection or not collecting. I mean, you’re an expert. I would trust your opinion on that certainly more than I would trust mine, so full stop. That’s why I asked if there were other black people that– if there was unanimous agreement amongst you. And I don’t mention like one weird dude in the corner that just happened to always– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 21:10 | No. We’re talking about systematic. |

| C.T. WEBB: 21:13 | Okay. So this is my issue with this. And then please, Seph, say something [laughter] so it’s not so much about [inaudible]. So this is my issue. I feel like this is the go-to, intellectual, rhetorical move of the late 20th and 21st century. And there are things that you’ve said in the conversation and that I’ll be specific about. If you saw more improvement, if you saw more movement. So to me, when I get into these conversations, it feels like a type of Gnosticism. It feels like an assumption that the world is corrupted and has been and continues to be. And I just can’t get on the same page with you if you say that nothing has changed, or there haven’t been– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:17 | But I didn’t say that nothing’s been changed. What I’m saying is the kind of progress. |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:18 | Okay. No, no. You saw if more movement. What kind of progress? People were– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:25 | White people looking at themselves. White folks looking at themselves, who identify as white, looking at the structures and the things that they embrace. |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:30 | You don’t think white– you don’t think there are a lot of white people looking at themselves? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:34 | I’m saying that– |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:35 | How many do you want? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:37 | No, no, no, no. Here. I think at the bottom of my patience [with?] the idea that you have is– you’re requesting something of me that others aren’t. |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:46 | What am I requesting of you? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:46 | –which is faith. |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:50 | I’m saying go on evidence. You don’t have to have faith. Go on evidence. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:53 | I’m going on evidence, and I’m actually going– I’m going on evidence, and I’m going on faith. Rhetorically, I think that when it comes to people who are invested in a particular kind of system, in saying that they need to look at themselves and to see how they are shaping the world doesn’t deny me– I’m still a part of that culture. We are still together. I’m saying do your work. I’m doing my work. Do your work. That’s what I’m saying. |

| S. RODNEY: 23:21 | So can I jump in here now? |

| C.T. WEBB: 23:23 | Yup. Full stop for me. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 23:24 | Sure [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 23:26 | Wow, that’s a lot to unpack. I’m going to start off with something that I ended up talking about the other week when I gave a talk at the New York Academy of Art with Sharon Louden. And I was speaking about– and by the way, as I do this, I’m not sure that I’m going to be able to rope in all that’s been said in the last 10 or 12 minutes [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 23:49 | Nor should you. |

| S. RODNEY: 23:50 | Right. Because there is a lot there. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 23:54 | Yeah. Quite a bit. |

| S. RODNEY: 23:55 | But one of the things that gives me a kind of avenue in – excuse me – is me talking about– in that talk at the New York Academy, I remember speaking about the distinction for me between my job and my responsibility. And I said my job at Hyperallergic is to cover the visual arts and performing arts, actually, and to give my opinion, to give my analysis. That is what Hrag and Veken, my bosses at Hyperallergic, want me to do. Explicitly they say this. That’s what they want. That’s what they count on. I consider it my responsibility– so it’s beyond my job description, right? I consider it my responsibility to cover the arts that concern or are produced by people of color and women because I know that they have been historically underserved, that historically, it’s just not fair. The arts ecosystem has been tilted towards white men. That distinction, I think, is important to me because it’s kind of the one that gets erased a little bit, or at least submerged in that conversation that Toni Morrison has with Charlie Rose. |

| C.T. WEBB: 25:32 | Charlie Rose. |

| S. RODNEY: 25:33 | Yeah. Because she’s making it sound like her job, right, is to do what she does in crafting these very complex pieces of fiction and really get and unpack the kinds of ideologies and assumptions that we make as human beings living in this culture now. Right? And it can be traced back to the cultures that she specifically represents in her novels– or have antecedents in those cultures represented in her novels. But her responsibility, she’s saying, “Well, that’s not my responsibility to do the work that white people should be doing.” On some level, she’s right. But she’s winning the battle at the expense of the war, I think. Because I will agree with Travis on this. The tendency, in my experience, is that people who make that argument– black people and people of color who make this argument, make it in that kind of smug way that begins to, again, demarcate out culture as belonging to specific racialized phenotypes or specific communities of shared ideology. |

| S. RODNEY: 27:03 | So a good example is Haru [inaudible]. Haru, who Steven and I both know, and who has co-written some stuff with me for Hyperallergic years ago, and we have a kind of professional relationship, he has said similar things in my presence. And I’ve always found with Haru that it comes off– and this could very much be my reading of him through having known him for the time I’ve known him. But it always comes off to me as smug. And it comes off to me as smug in the same way that Lawrence Harding – who again, you all know Lawrence – comes off to me as smug when he says, “Yeah. I don’t bother voting because the whole system is stupid. It’s not going to– My vote isn’t going to change, blah, blah, blah.” And they both have in their own ways validity in their arguments. Lawrence will argue that his vote, particularly in New York City and New York State, doesn’t change much. Now, there’s some validity to that. Haru will argue that there’s particular kinds of work that white people need to do that is not his responsibility, not his job. They should take care of their own shit. I also kind of in a limited way can agree with that. |

| S. RODNEY: 28:25 | But the problem is that that attitude presupposes that if you merely take care of your plot of land, right, that that’s enough. And it isn’t. It isn’t ever enough. Because what happens is, we never know– and even if Haru’s community is his own community, and it doesn’t necessarily connect to the communities of the white people he talks– or it’s not explicitly or evidently connected to the communities that he’s talking about, that he despises, we are connected. We are connected socially and economically and politically. We absolutely are. And my problem with that position is that if you take it as that’s not my responsibility [inaudible] job, because it’s not your job, but if you don’t take it on– you don’t conscientiously take it on as your responsibility, you leave the land to people like Donald J. Trump. It just happens. |

| S. RODNEY: 29:23 | This is what happens. When you say forcefully and loudly to everyone who exists within the reach of your voice that it’s not worth making this fight because I’m trying to survive as a black man out here every day, la, la, la, again, that has validity, but it has very limited utility, right? Because ultimately, if you don’t do the work, my question is is it going to happen? And I can tell from my own experience in this country that it typically does not, that if you do not yell yourself hoarse saying that this is a collective endeavor to redeem the soul of the white misanthropic United States– even James Baldwin said this. It is a collective endeavor. |

| C.T. WEBB: 30:24 | Oh, yes. He did. |

| S. RODNEY: 30:28 | I can not mark out certain plots of land or certain plots of [inaudible] or political land and say, “This belongs to me. This is the garden I need to tend, and I can let the rest of it go to hell.” It can’t. It just doesn’t work. |

| C.T. WEBB: 30:43 | I want to actually give you the last word, Steven, because we’ve got about two or three more minutes, so I want to get– but I want to say something, actually, to piggyback on Seph and to say something even more provocative and pointed about it, and maybe we can take the conversation into our next one. That position is the widest position that I know [laughter]. The idea that it is white people’s job to fix themselves and that we’re all fine over here is a– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 31:12 | Oh. |

| C.T. WEBB: 31:13 | No. Okay. Take out that we’re fine. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 31:15 | Hmm-mm. Take it out. |

| C.T. WEBB: 31:16 | That’s implied. That is implied. Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 31:19 | You’re being provocative. Go ahead. |

| C.T. WEBB: 31:19 | That’s implied. It’s implied. That is a white position. That comes from a position that is a white ideology. You can dress it in whatever skin color you want. That is a white ideology. Its metaphysics are white. That is the whitest white [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 31:41 | I love that phrase because it reminds me of that scene from The Invisible Man, right, where he dips his fingers in [inaudible]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 31:46 | Yes. Yes. That’s what I was thinking. The whitest white. Yes. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 31:48 | Oh, no [crosstalk]. He’s invisible. He’s invisible to whom? He’s invisible to whites. He’s not invisible to black people. I get that. I [crosstalk] for that. |

| C.T. WEBB: 31:55 | Okay. Okay. So, Steven, you run the table. You get the last two or three minutes. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 31:59 | Let me just say I’ll run the table. I’m tapping my table right now [laughter]. So very provocative and thoughtful ways of helping me think through some of the things that I think about when it comes to responsibility. So I appreciate both of your arguments. I chose not to call you James Baldwin one and James Baldwin two because that’s where you guys were sort of steering your arguments or had similar arguments that I read over the years by James Baldwin. I wonder, though. I did think about the smugness part of it, and in the sense that if that were removed, would the argument still hold the same amount of clarity, but also whether or not it’s the audacity of someone who is not white to say, “I have a position about this.” And this position here is– this is a way to think about it. Travis almost wants you to end the podcast with your whitest white, white, white position [laughter] because it’s very funny because it also makes me think of, “well, that’s just a perspective.” It’s a perspective. What I love about what you both said is community and communal response, because I love that and because I feel like I’m a part of a communal response through my work. But what I also am assaulted with is white misanthropy. I’m assaulted with black misanthropy. We’re talking about this idea of a hatred of the body. I do not have that hatred. That is not my point. |

| C.T. WEBB: 33:26 | Yeah. Me neither. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 33:27 | But this is not my work. My work is to be a human. Now, if that helps another white misanthropic or a black misanthropic or a Chinese or whomever, then I’m good with that. But what I’m advocating for is a certain responsibility. That’s what I’m advocating for. |

| C.T. WEBB: 33:42 | Thank you very much for that. |

| S. RODNEY: 33:44 | Yeah. I think we need to pick that up the next time, and I’m really looking forward to talking this a little bit further– |

| C.T. WEBB: 33:48 | Cor. |

| S. RODNEY: 33:48 | –especially working on some of the things that you had us read in this last week, Steven. |

| C.T. WEBB: 33:55 | Wow, and we didn’t get– so I’d like to actually lead off the next one with– and going into Steven’s stuff I think is a good idea too, but you would send us the LA review of books essay that we didn’t– I mean, you kind of touched on it with the– you touched on it a little bit when you drew out the phenotype being a terminology. So maybe we can– you can lead with that because Steven and I did a lot of jawing at each other [laughter], so. Or with each other, I should say, so. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 34:18 | Oh, it was lovely community [crosstalk] communication. |

| C.T. WEBB: 34:21 | Oh, yeah. For sure. Absolutely. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 34:23 | I’m being funny, but no, I mean that. |

| C.T. WEBB: 34:24 | Me too. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 34:25 | I want to hear and think through this responsibility thing. |

| S. RODNEY: 34:27 | Yeah. Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 34:28 | So next episode is Seph [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 34:31 | All right, gentlemen. Thanks very much. |

| C.T. WEBB: 34:33 | All right. Sounds good. Thanks a lot. Bye-bye. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 34:34 | Thank you. [music] |

References

First referenced at 05:38

“MONSTER’S BALL is a hard-hitting Southern drama tempered by a story of powerful life-changing love. It is the story of Hank (Academy Award winner, Billy Bob Thornton), an embittered prison guard working on Death Row who begins an unlikely but emotionally charged affair with Leticia (Academy Award winner, Halle Berry), the wife of a man under his watch on The Row.” Amazon

Episode 0101 – Comedy: Patrice O’Neal, Laughing Because It Hurts

Patrice O’Neal died in 2011, but his comedy is still hot. Stories that turn a bitter reality into laughter is this week’s subject. Should there be a limit on what comedians can say for a joke?

Comedy: Maria Bamford, How to Maintain Mental Health

The cliché goes that “laughter is the best medicine,” but the idea’s been around for thousands of years, so it’s probably best to call it “wisdom.” How can comedy help us cope with trauma?

Episode 0098 – Comedy: Offensive Comedy and Its Virtues

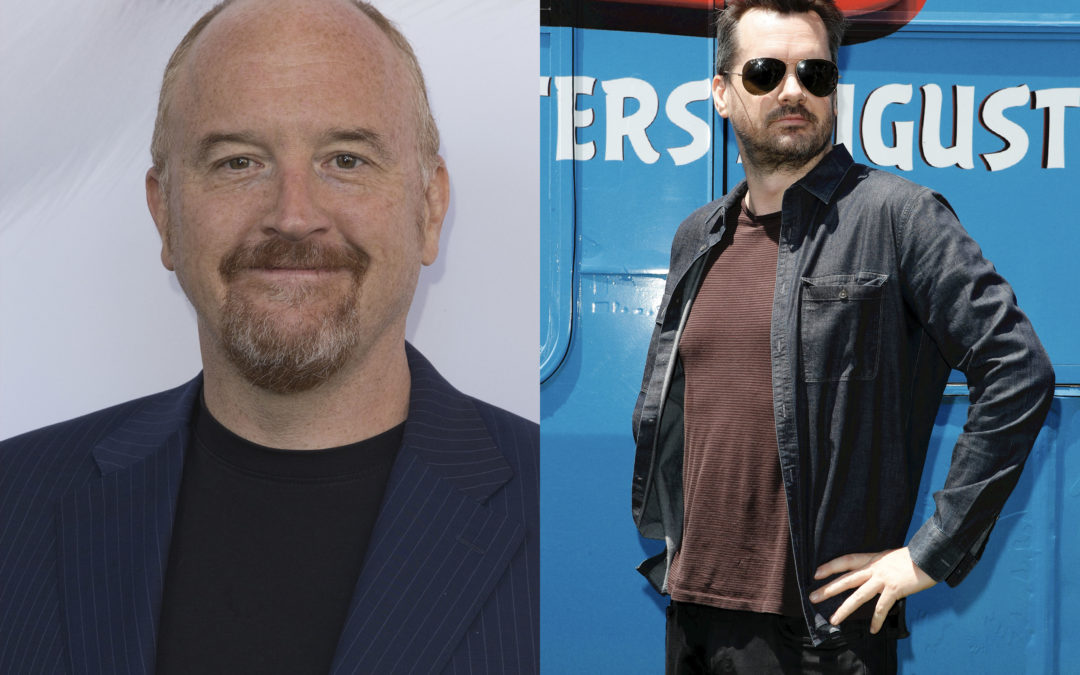

There’s laughing at yourself, and then there’s laughing at others. While the former is virtuous the latter is indispensable to group cohesion. In this episode the hosts talk about Jim Jefferies and Louis C.K. What are the limits of comedy?

Humor: What’s so funny?

The hosts take a personal look at what they find funny and why. Fair warning, political sensitivities aren’t off-limits.

0 Comments